– by Suhas Chakma*

India and member states of the European Union have been facing serious confrontation over hum an rights and counter-terrorism issues. India has been at loggerheads with individual countries like Denmark, Portugal and the United Kingdom but soon, it may turn into an EU-India issue. The concerns do not relate to typical EU public statements or official démarches on India’s human rights record, rather the issues and concerns are beyond the jurisdiction of all the governments concerned.

In July 2012, India downgraded its diplomatic relations with Denmark and instructed senior government officials not to interact with the Denmark embassy officials because of the failure of the government of Denmark to file an appeal before the Danish Supreme Court against the Danish High Court order that barred extradition of Kim Davy, prime accused of the Purulia arms drop cases of 1995. India’s position is that Denmark should have filed the appeal — a technically right contention — after India assured to give “legally binding” commitment to provide an exclusive prison to Davy during trial for filing the appeal before the Danish Supreme Court.

The moot point is whether the assurance addresses the Denmark High Court’s order to bar extradition of Kim Davy on the grounds of India’s poor prison conditions and failure to ratify the UN Convention Against Torture (UNCAT). As a ratifying party to the UNCAT, Denmark cannot extradite any person without meeting the legal obligation under Article 3(1) of the UNCAT which stipulates that “No State Party shall expel, return (“refouler”) or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture”.

The government of India did little to address the grounds raised by the Denmark High Court and has even failed to respond to the Public Interest Litigation filed before the Kolkata High Court as to the steps taken by the government of India to ratify the UNCAT to facilitate the extradition of Kim Davy. Without addressing the grounds taken by the Danish High Court judgment, India was essentially asking Denmark to certify that there is no “consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights” as required under Article 3(2) of the UNCAT.

The reports of India’s National Human Rights Commission on custodial deaths leave little space for Denmark to file an appeal should India’s assurance to Denmark’s Supreme Court be taken seriously considering the absolute messy situation with respect to extradition of Abu Salem, the prime accused in Mumbai blasts of 1992. After being arrested by Interpol in Lisbon in September 2002, Salem was extradited to India in November 2005 after India under the “Rule of Speciality” assured that Salem will not be charged with offences that attract death sentence and more than 25 years imprisonment. Salem has since been facing trial in India.

However, in September 2011, the Portuguese High Court cancelled the extradition of Salem on the ground that he was tortured in custody following extradition to India

and charged with death penalty offences. The Indian government appealed against the order of the High Court before the Portuguese Supreme Court which upheld the order of the High Court. In July 2012, Portugal’s Constitutional Courts dismissed the government of India’s appeal on the ground that India could not suo moto approach it challenging the Supreme Court order.

India’s Central Bureau of Investigation has indicated that Salem will not be repatriated back to Portugal. While the Portugal’s Constitutional Court’s dismissal remains technical in nature, if Salem is indeed not repatriated, the government of Portugal is most likely to be directed by the courts to pursue repatriation of Salem. India should bear in mind that on February 17, 2011, the Supreme Court of India stayed trial for all fresh cases, which invoked a death penalty or jail for 25 years. However, it remains also a fact that Delhi and Mumbai Police had slapped charges invoking death penalty on Salem.

If indeed Salem’s extradition goes awry, it will have serious implications for extradition of Kim Davy; as also in the case of Tiger Memon, prime accused of the 1993 Surat bombing, notwithstanding the consent of the government of India to allow a British human rights expert to visit the prison in Surat to

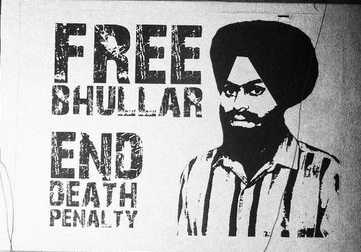

Bhullar was taken into custody while in transit at Frankfurt Airport on the way to Toronto. He was deported to India on January 19, 1995, tried under the Terrorists and Disruptive Activities Prevention Act and convicted to death in 2000 solely based on his confessional statement made before the police without any corroborative evidence. While confession made to a police officer is admissible under the TADA, it is against India’s Evidence Act and Article 14(g) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In fact, one of three judges of the Supreme Court, Justice MB Shah dissented against awarding death penalty to Bhullar. Germany could not have deported Bhullar if it was known that he would be given death penalty.

India claims itself as the largest democratic country and rightly takes offence for any insinuation against its judiciary. Therefore, the government of India should be able to understand the legal compulsions of Denmark, Portugal and the United Kingdom where the orders of the national Supreme Courts can further be challenged before the European Court of Human Rights. India’ diplomatic brinkmanship with Denmark, Portugal and the United Kingdom is unlikely to help. It is akin to Norway asking the government of India to annul the Supreme Court judgment over the 2G spectrum scam just because Norwegian people have invested in Telnor’s partner Uninor.

No other government knows better than the government of India that a Supreme Court judgment cannot be over-turned by the Executive and therefore, a presidential reference on the 2G spectrum scam is being heard currently by the Supreme Court. There cannot be any shortcut or one-upmanship game with the judiciary in any country governed by the rule of law. India has no other option but to comply with the EU human rights standards if it seeks cooperation of the EU governments who cannot overrule their judiciary like the government of India with respect to its judiciary. If this basic fact is understood, there is unlikely to be any confrontation between the largest democracy and the largest democratic bloc in the world.

* The writer is director, Asian Centre for Human Rights.