Sikh Genocide 1984 » Sikh News

Exposing The Powerful & Influential Men Behind 1984 Sikh Genocide

January 23, 2018 | By Sikh Siyasat Bureau

by Pav Singh*

One of the earliest allegations of Congress complicity was published in The New York Times on November 4. The article, filed the day before by Barbara Crossette while reporting from the killing fields of Trilokpuri, noted how middle-class Sikhs and Opposition politicians laid the blame on Congress party members for inciting the killers at the local level.

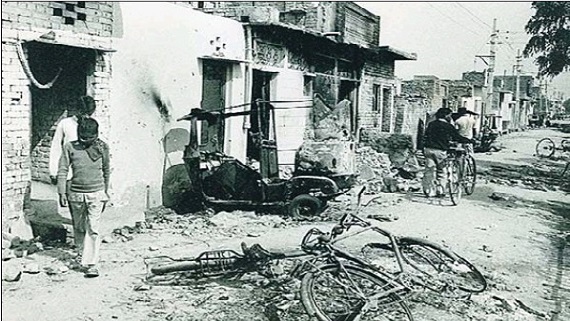

A Charred remains of a Sikh colony in the aftermath of Sikh Genocide of November 1984 [File Photo]

On 8 November in The Times, Delhi correspondent Michael Hamlyn’s article, “Opposition leaders blame Congress party for violence against Sikhs”, included an interview with former Indian Prime Minister Chaudhary Charan Singh. An erstwhile Congress politician who had been an outspoken critic of Nehru’s economic policies and was jailed by Indira Gandhi during the Emergency, he told Hamlyn that Congress party legislators had “incited people they had brought in from the outskirts to burn, loot and if possible murder Sikhs.”

The names of those considered responsible first appeared in a joint report released by the People’s Union for Democratic Rights and People’s Union for Civil Liberties on November 19, 1984. In “Who are the Guilty”, it was claimed that activists had been informed by both Hindus and Sikhs (many of whom had been Congress supporters) that “certain Congress (I) leaders played a decisive role” in organising the violence. The report named sixteen politicians alleged to have instigated violence or protected alleged criminals, and thirteen police officials alleged to have neglected their duty and having aided or participated in the violence.

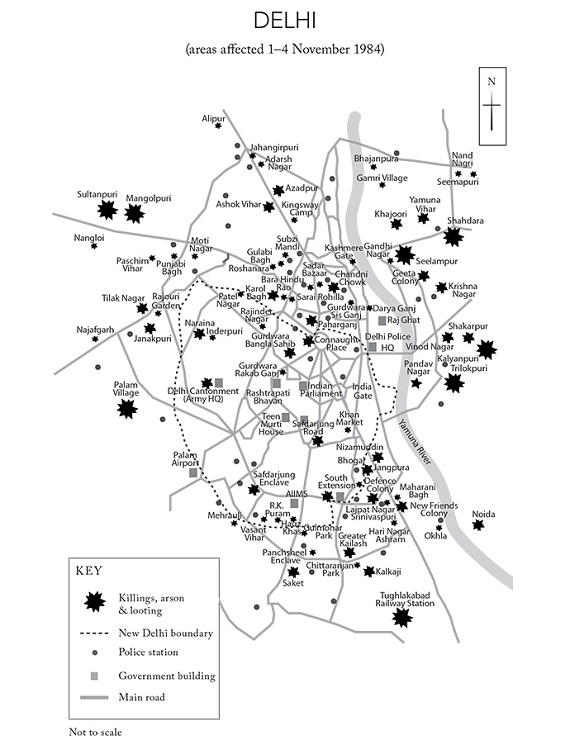

Map of the affected areas in Delhi (Source: 1984: India’s Guilty Secret)

Shortly after the Congress party’s landslide victory in the December 1984 election, social activist Amiya Rao estimated in a report published by Citizens for Democracy that at least 150 of the ruling party’s members — including leaders, MPs and city councilors — had played an active role in what she described as “not an ordinary holocaust [but] an organised orgy”. The killings, she contended, were scheduled to start on November 1 following a series of meetings held the previous night around Delhi at which Congress leaders allegedly gave the “final touches” to the plan that had already been prepared “with meticulous care”.

One of the key figures alleged to have been present at these clandestine gatherings was Arun Nehru, a distant cousin of Rajiv Gandhi who had left his job in the private sector to enter politics at the behest of Indira Gandhi. In the Congress comeback in 1980, he was elected as an MP for the Rae Bareli constituency in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, then a stronghold for his party. He became a key advisor to the Gandhi family, reportedly playing a pivotal role in developing and implementing Operation Blue Star in June 1984 {Indian Army’s Attack on Darbar Sahib, Amritsar}.

Rumours have circulated for decades about Nehru’s alleged key role in the organisation and implementation of the November 1984 massacres. A civil servant, who had the night before saved a Sikh motorcyclist and his father, went to see Nehru on November 1. When he demanded that the Army be deployed, Nehru’s demeanour was “frighteningly casual” as he explained that he and the Congress party were doing everything they could.

Source: India Today archive.

Darker and even more disturbing allegations were levelled by those with connections in India’s defence and intelligence communities. According to one source, the massacres had perversely been codenamed “Operation Shanti” (shanti being Hindi for ‘peace’). Apparently, it was initially planned for around November 8 to coincide with the birth anniversary of the first Sikh Guru, Guru Nanak Dev Ji — at such a time large gatherings of Sikhs at gurdwaras across the country would make for easy targeting.

However, the assassination on October 31 offered the opportunity to bring the killings forward. The source claimed that Arun Nehru took command of the operation and issued directives to Congress members of Parliament, councillors and Youth Congress workers. Delhi police reportedly were to either stand aside or assist where needed.

The most damning revelation, though, came in 2014. The former petroleum secretary, Avtar Singh Gill, recalled how he had been warned about the violence in the morning of 1 November. Hotelier and a friend of Rajiv Gandhi, Lalit Suri, told him what he knew: “Clearance has been given by Arun Nehru for the killings in Delhi and the killings have started.” He went on to describe how the gruesome plan was to be implemented:

The strategy is to catch Sikh youth, fling a tyre over their heads, douse them with kerosene and set them on fire. This will calm the anger of the Hindus.

Suri warned Gill to remain vigilant even though his name was not on the Delhi gurdwara voting lists: “They have been provided this list,” cautioned Suri. “This will last for three days. It has started today; it will end on the third.” According to intelligence sources, Nehru had allegedly overseen the gathering of voting lists in the lead up to Operation Blue Star {Indian Army’s Attack on Darbar Sahib, Amritsar} to help contain any backlash from Delhi’s Sikh community once it had taken place. Prior to Operation Blue Star {Indian Army’s Attack on Darbar Sahib, Amritsar}, Nehru had discretely sounded out associates with Sikh connections about the possible repercussions of a military assault on the Golden Temple of Amritsar {Darbar Sahib, Amritsar}. Another senior Congress politician who is said to have had done the same was Hari Krishan Lal Bhagat.

Teetotal and a strict vegetarian, Bhagat was a political big-hitter with close connections to Indira Gandhi. Following a stint as the capital’s deputy mayor, his rise in the 1970s saw him become one of the most important personalities in Delhi’s political scene. He held several ministerial positions, and by 1984 he was serving as the minister of information and broadcasting.

During the anti-Sikh pogrommes, he was allegedly the one of the most visible senior Congress ministers involved. Eyewitnesses in his East Delhi constituency reported seeing him over the four days inciting people to commit murder, distributing money to mob leaders even leading some of the gangs himself.

On his way home after the day’s work around 8pm on October 31, a Hindu vegatable-seller, Sukhan Singh Saini, joined a crowd of men near his home in Shakarpur. He claimed to have recognised those present, especially Bhagat, whom he knew well. The minister was handing out bundles of rupees to the ringleaders with instructions to “keep these two thousand rupees for liquor and do as I have told you”. Bhagat assured them: “You need not worry at all. I will look after everything.” After warning a Sikh friend early the next morning, Saini saw Sikhs being beaten in the streets by several of the men from the night before.

One of the widows, Ajay Kaur, filed an affidavit in 1984 naming Bhagat. She claimed to have seen Bhagat, on the night of October 31, telling a crowd that the police would “not interfere for three days. Kill every Sikh and do [your] duty to Mother India”.

Later on the night of October 31, Bhagat was apparently seen by Wazir Singh, a boy of eleven who lived with his grandmother in Himmatpuri (not far from the Kalyanpuri police station), coming out of the house of a Congress worker, Rampal Saroj. It was claimed that he had just held a meeting with local party members, and as he left, they raised anti-Sikh slogans. The following morning, Wazir Singh noticed Saroj leading an armed mob about fifty-strong including several Congress workers. It was clear to the boy that Bhagat had “given instructions in the meeting to kill the Sikhs”. Saroj also allegedly took part in the massacre in neighbouring Trilokpuri.

Bhagat reportedly was next sighted on the morning of November 1 by Gurmeet Singh, a taxi stand owner and a driver from Laxmi Nagar. Singh was among a group of a hundred armed Sikhs who had assembled at the local gurdwara to defend themselves against a similarly sized mob that had attacked their homes earlier. Just after 11am, a white Ambassador car approached at the head of a cavalcade of nearly 200 armed people yelling anti-Sikh slogans on scooters, motorbikes and auto-rickshaws.

It parked nearby and, to Singh’s surprise, Bhagat alighted from the car. He knew the minister well as he was a strong Congress supporter — he had even gave his taxi for free for Bhagat’s election rallies. As six policemen (who had up to that point been watching the mob at work) approached the minister, Bhagat allegedly asked them why “they” — pointing towards the Sikhs — had not yet been killed? Having incited the murderers, he got back into his car and drove off.

As Shital Singh tried to escape after his home near Gamri Village had been torched, he was surrounded by a large group of men at a crossroads. His brother Satu Singh (who had cut his own hair to avoid detection) saw him falling to the ground after being stricken by a brick. It was at this point that Bhagat emerged from the crowd. Wearing his distinctive black glasses, he allegedly gave the order to kill Shital Singh, spurring on the furious crowd with the words: “He is the child of a snake, kill him, don’t spare him, if you spare him, he will give a lot of pain.” Satu Singh then saw that someone threw what looked like “some chemical” on his brother’s face, which ignited instantly. Next, a truck tyre doused with kerosene was thrown over him and set alight. As the fire caught hold, Bhagat was reportedly heard taunting his victim: “Call your Guru Gobind Singh, I want to see him, where is he?” Shital Singh replied: “Guru Gobind Singh is with me…do whatever you want to do.”

Bhagat’s role shifted to one of coercion in the months after the massacres, allegedly threatening victims or promising them incentives in order to coerce them to withdraw their statements naming him. Housing was offered to the residents of Block 32 in the Trilokpuri colony on several occasions in August 1985 in exchange for two dozen affidavits stating that no Congress workers were involved in the attacks. Others, including Satnami Bai who had named Bhagat as the one instigating mobs, withdrew their allegations under duress.

Victim Darshan Kaur.

One of those who still had hopes of seeing justice served is Darshan Kaur, a survivor of the Trilokpuri atrocities. On the night of the attack, as she had crouched down to take cover inside her house, she claimed to have heard Bhagat egging on the assailants: “Whatever you need — chemicals, powders, anything — I will give them to you.” They discovered her husband hiding in a small landing in the attic and dragged him into the street, where he was immolated. In total, she lost twelve members of her family that day.

Besides naming Bhagat, she also claimed that the local Congress leader, Rampal Saroj, was the chief instigator of the deadly crowds who was witnessed calling out the rallying cry, “No one should be spared”. Despite other witnesses withdrawing their statements, Darshan Kaur stood her ground, even when men sent by Bhagat offered her large sums of money in exchange for her silence. She has been physically attacked and intimidated in the years, but has refused all advances.

Bhagat was also implicated in the death of a Delhi Police head constable, Niranjan Singh. He had been on duty at Shahdara railway station on November 1 until he was chased down and lynched, and his body set ablaze outside his house. The next day, his teenage son and son-in-law were also killed. Niranjan Singh’s widow, Harminder Kaur, survived and filed a case against Bhagat and others in 1996. While the judicial process moved along slowly, she faced constant harassment from the police. As the evidence against Bhagat was deemed insufficient, the case against him was dropped in 2000. However, three other people were eventually convicted for the murders in 2007.

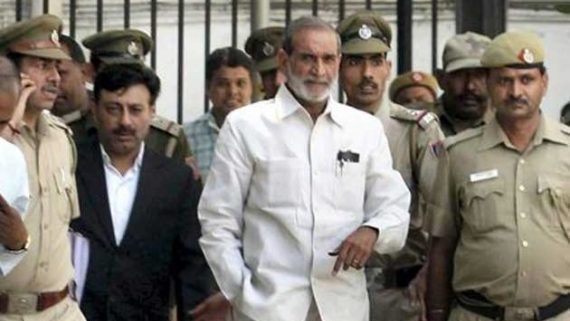

Another of the alleged Prime Minister’s men was Sajjan Kumar. Initially a roadside tea-seller and later a bakery-owner, he was said to have been handpicked by Sanjay Gandhi to enter politics. In 1984, he was MP for the constituency of Mangolpuri in Northeast Delhi. Sajjan Kumar was named by several survivors as presiding over the pogroms in a number of Delhi suburbs.

Sikh Genocide 1984 accuse Sajjan Kumar.(File Photo)

On October 31, Sajjan’s men canvassed homes in West Sagarpur, South-west Delhi, to collect Rs 15 from each household towards the construction of a new road. At the same time they also checked the ration cards of Sikh families. Come the morning, the local gurdwara and Sikh-owned shops were burnt down before Sikh residents themselves also came under attack.

In a park in Sultanpuri, adjacent to Kumar’s Mangolpuri constituency, Cham Kaur claimed to have heard him address a gathering of local residents: “Sikhs had killed Mrs Gandhi; therefore, you kill them, loot their goods and burn them alive.” Kumar was next spotted allegedly the following day personally directing mobs. Several witnesses also claimed to have seen him involved in the violence. Joginder Singh claimed that he recognised Kumar and other Congress leaders (including Jai Kishan, a former member of the legislative assembly) amongst the murderers as they dragged his cousin and other Sikhs from their homes: “Sajjan was laughing and ordering the mob to search for Sikhs and kill them,” he recalled. “I was a clean-shaven Sikh so they were unaware of the fact that I am a Sikh.”

During this attack, Sajjan Kumar allegedly kicked Kamla Kaur aside as she begged him to spare her husband and son. He was also accused by Bhagwani Bai of orchestrating the deaths of her sons, who were burnt in front of her under Sajjan Kumar’s orders.

On November 1 at Nangloi, again not far from his constituency, Kumar was seen allegedly inciting the crowd to attack Sikh homes. One of his intended victims was Gurbachan Singh, who had taken up a defensive position on the second story of his house with his brothers:

“About ten police officials were also present at the spot and they were encouraging the mob to kill us. I saw Sajjan Kumar, the then Congress MP of our area standing amongst the mob and he was directing the mob to attack us with more and more force and kill us.”

After witnessing the killing of his father and two other members of his wife’s family, he and his brothers, who were armed with swords, managed to cut their way through. When he tried to report the murders at the local police station two days later, he was “made to fill out a pre-formatted FIR. In the blanks next to who led the mob, the word ‘unknown’ had been written”. Kumar’s name was never entered into police records.

On November 2, Sajjan Kumar was allegedly seen in a police jeep in Palam, South-west Delhi announcing: “No Sikh should live. If anyone gives shelter to Sikh families, their houses will be burnt.” That evening he was seen in nearby Raj Nagar allegedly inciting the attackers “to kill more Sikhs”. At least 340 Sikhs were killed in Raj Nagar, an area covered by Delhi Cantonment police station. The diary entries of the police, though, tell a different story: “End of the day 1st and 2nd of November: all clear, nothing to report.”

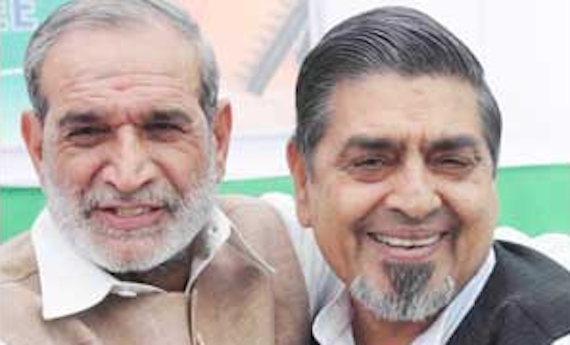

Three decades on from the massacres, Jagdish Tytler, another of Sanjay Gandhi’s close associates and an active member in the Congress party’s youth organisation, was specifically named in a WikiLeaks American Embassy cable as having allegedly “played a particularly grotesque role, competing with local Congress party leaders to see which wards could shed more Sikh blood.” Witness Jasbir Singh claimed he had heard the MP for the Delhi Sadar constituency near Old Delhi rebuking his men for the “nominal killing of Sikhs in his constituency”. He subsequently fled to the US after he had lost twenty-six relatives in the carnage.

The alleged scolding dished out by Jagdish Tytler exposes a sickening arrogance:

“Because of you, I am ashamed to look at Sajjan Kumar’s constituency in the north or HKL Bhagat’s constituency in the east. Colony after colony of Sikhs has been destroyed but in my area so few Sikhs have been killed. I had promised that maximum Sikhs would be killed in my colony.”

Jagdish Tytler was also reportedly seen on November 1 morning by Surinder Singh, a Sikh granthi (scripture-reader) of the Pul Bangash Gurdwara in North Delhi. As he watched from the safety of the top floor, he claimed he could see that Tytler was in control of a crowd armed with staffs and iron rods. On his command, they set fire to the building and killed three Sikhs inside:

Sajjan Kumar (L) and Jagdish Tytler (R).

He incited the mob to burn the Gurdwara and kill the Sikhs. Some people in the mob were carrying flags of Congress. They were raising slogans like “we will take revenge”, “Sikhs are traitors”, “kill! burn!”. Five to six policemen were also with the mob.

Surinder Singh made it to safety that night with the help of his Muslim neighbours.

A few days later, Tytler was further compromised when he burst into the office of police commissioner, Subhash Tandon, just as he was in the middle of a press briefing with Indian and foreign journalists. Tandon had just categorically denied the allegation that Congress MPs had tried to get their men, who had been jailed on suspicion of committing acts of violence, released.

Just as he had finished stating that he had never received any calls or visits by any politician, Congress or otherwise, Tytler barged in along with three followers, demanding at the top of his voice: “What is this Mr Tandon? You still have not done what I asked you to do?” Realizing the faux pas, he said to the embarrassed commissioner: “By holding my men you are hampering relief work.” To the bemused reporters he boasted: “There is not a single refugee in any camp in my constituency. I have made sure that they are given protection and sent back home.” According to one of the journalists present, the incident left the commissioner speechless and them in no doubt about Congress interference in police work.

Another Congress MP who is said to have made a public show of his sway over the police was Kamal Nath. Again, he had close ties to the Gandhi family, having attended the Doon School (known as the Eton of India) with his friend Sanjay Gandhi. He was elected as an MP in 1980 in the constituency of Chhindwara in the central state of Madhya Pradesh.

On November 1, 1984, Nath was accused of allegedly leading an armed mob that laid siege to Gurdwara Rakab Ganj, a major shrine in the heart of New Delhi only a few hundred yards from the nation’s Parliament buildings. It is historically significant as it commemorates the spot where the ninth Sikh Guru’s body was cremated following his execution by the order of a Mughal emperor in 1675. A member of the gurdwara staff, Mukhtiar Singh, had seen an angry crowd approaching. Then they began pelting stones at the shrine and at those inside its boundary walls. Delhi Police officers were present but showed no interest in intervening. Within half an hour, the crowd swelled in size to around a thousand-strong.

At noon an attempt was made to storm the building, but staff and devotees collectively managed to push the mob back. An elderly Sikh devotee then decided to appeal for peace and approached the mob with folded hands. He was dragged out of the boundary and severely assaulted with stones. While he lay on the ground, white powder — most probably phosphorus — was thrown on his body causing it to catch fire. His son ran to attempt a rescue but, like his father, was also injured and set alight. The Sikhs managed to drag them, still alive, into the safety of the gurdwara but they died a few hours later owing to lack of medical treatment — the shrine being surrounded on all sides and the police unresponsive to calls for assistance.

Further attacks were mounted. With the assistance of several police officers the mob eventually succeeded in entering the sacred building. Mukhtiar Singh and others drove them back again, this time pelting the intruders with the same stones that had been hurled at them. Another tactic used to hold them back was setting off fire crackers with a gun-like launcher, which the mob mistook for actual gunfire.

Still though, more attacks followed. In desperation one of the Sikhs fired his licenced pistol into the air. It was soon after this that a much larger force approached the gurdwara, Mukhtiar Singh claimed he clearly saw Nath and other Congress men including Vasant Sathe, former minister of information and broadcasting, at its head. According to him, the police fired several rounds at those inside the gurdwaras after receiving instructions from Kamal Nath.

Observing from the street was a crime reporter for The Indian Express, (Monish) Sanjay Suri. He had set out that morning on his scooter and reached the gurdwara by following a combination of the columns of smoke that rose above the city and some tip-offs from police contacts. On arriving he stated under oath to have seen Nath standing near to the front of the crowd, which was repeatedly surging forward as it attacked again and again. Among the police personnel, who were watching on, there was additional commissioner of police, Gautam Kaul, who was carrying a bamboo shield. It was clear to Sanjay Suri that the management of the crowd had been left to Kamal Nath — when he signalled, the crowd listened. This level of control led Suri to conclude that they were Congress party workers who accepted him as their leader.

Lalit Maken, whose father-in-law, Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma, would later become India’s president, was seen reportedly paying mob members a hundred rupees each, plus a bottle of liquor during the carnage. The Delhi metropolitan councillor with a trade union background was allegedly seen giving instructions to those indulging in arson near Azadpur in North-west Delhi from inside his white Ambassador car.

One of those reported to have used voter lists to identify Sikh targets was Dharam Dass Shastri, MP of Karol Bagh, a heavily commercial neighbourhood in West Delhi. One survivor who had fled to Amritsar following the attacks in Karol Bagh reportedly told a reporter for The New York Times that he had seen Shastri allegedly in action. “I saw it happen, and I saw this man Shastri leading and directing the crowd,” said Jitinder Singh. “He had lists.” From the roof of his house, Davinder Singh claimed he saw Shastri and a senior police officer provoking a mob to attack Sikhs. Amrik Singh, owner of a nearby electrical-shop, saw him ordering a large group of men to set Sikh properties and businesses on fire and to annihilate Sikh men, women and children. Their rampaging led them to also attack a local gurdwara, urinating on copies of the Sikhs’ holy scripture.

A resident of Karol Bagh, Chuni Lal, overheard a local Congress worker— whom Shastri had visited at his home the night before — allegedly encouraging a group of youths to seek revenge from Sikhs for the death of Indira Gandhi. He apparently gave reassurances that the police had been instructed by Shastri not to arrest any Hindus who looted, committed arson, or even killed Sikhs. Shastri was later seen reportedly in a heated exchange with police at the local police station, attempting to secure the release of 300 supporters who had been arrested for looting. The MP denied the allegation, insisting that he had “only tried to gain the release of members of local vigilante groups that appeared across New Delhi to defend their neighbourhoods after the police failed to do so”.

One of the most senior politicians to be embroiled was PV Narasimha Rao. This lawyer-turned-politician rose to prominence in the 1970s with several diverse ministerial portfolios in the Cabinets of both Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. As the minister of home affairs in November 1984, Rao was responsible for the maintenance of the nation’s internal security, which included law and order. He was therefore responsible for the security of the country’s citizens.

Several prominent individuals, including senior politician (and later prime minister) Chandra Shekhar and Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson, Rajmohan Gandhi, met PV Narasimha Rao to personally urge him to call out the Army. But his alleged casual approach in handling the violence, ignoring requests to deploy the Army, shocked a delegation of several notable citizens — including future prime minister IK Gujral, war veteran General Aurora and the author Patwant Singh.

As PV Narasimha Rao allegedly played cool, nearly 200 houses in Block 32 of the Trilokpuri colony were being decimated.

PV Narasimha Rao’s decision to choose party over duty followed a call allegedly from the Prime Minister’s office instructing him to do nothing about the killings that had just begun in what one commentator described as his “vilest hour”.

Delhi’s former lieutenant governor, PG Gavai, would later state publicly that this future prime minister of India “hid like a rat” when the violence began to engulf large parts of the country. Throughout the entire period, he failed to visit even one affected area.

Note: The above write up is reproduction of excerpts from author Pav Singh‘s book titled ‘1984 India’s Guilty Secrets‘ which is jointly published by Kashi House (UK) & Rupa Publications (India).

* Clarification: Text/terms in { } are inserted by the Sikh Siyasat News (SSN).

To Get Sikh Siyasat News Alerts via WhatsApp:

(1) Save Our WhatsApp Number 0091-855-606-7689 to your phone contacts; and

(2) Send us Your Name via WhatsApp. Click Here to Send WhatsApp Message Now.

Sikh Siyasat is on Telegram Now. Subscribe to our Telegram Channel

Related Topics: 1984 Sikh Genocide, Indian National Congress, Indian Politics, Indian State